Composition

What Is the Moon Made Of?

The Moon is a differentiated world. This means that it is made of layers with different compositions. The heaviest materials have sunk down into the Moon’s center, and the lightest materials have risen to the surface. Studies of lunar gravity, rotation, and quakes have helped us to understand the Moon’s layers.

The Lunar Core

At the Moon’s center is a dense, metallic core. This core is largely composed of iron and some nickel. The Moon’s core is relatively small (about 20% of its diameter) compared to other terrestrial worlds (like Earth) with cores measuring closer to 50% of their diameters.

The Lunar Mantle and Crust

Above the core are the mantle and crust. Differences in compositions between these layers tell a story of the Moon being largely, or even completely, composed of a great ocean of magma in its very early history. As the magma ocean began to cool, crystals formed within the magma. Chunks of denser mantle minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene, sank down to the bottom of the ocean. Lighter minerals crystallized and floated to the surface to form the Moon’s crust. The lunar mantle, with a thickness of roughly 1350 km, is far deeper than the crust, which has an average thickness of about 50 km.

The lunar crust is thinner on the side of the Moon facing the Earth, and thicker on the side facing away. Researchers are still working to determine why this might be.

Lunar Terrain

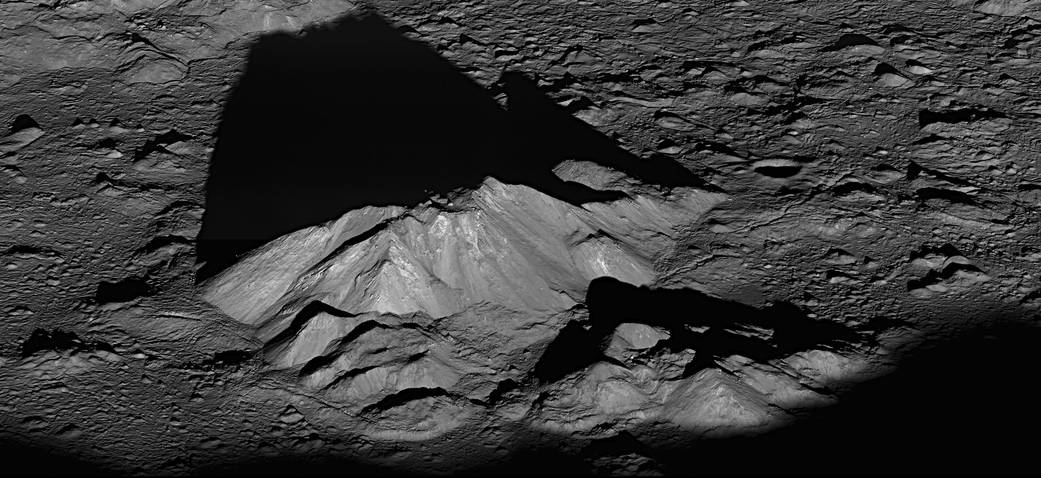

The light areas of the Moon are known as the highlands. The dark features, called maria (Latin for seas), are impact basins that were filled with lava between 4.2 and 1.2 billion years ago. These light and dark areas represent rocks of different composition and ages, which provide evidence for how the early crust may have crystallized from a lunar magma ocean. The craters themselves, which have been preserved for billions of years, provide an impact history for the Moon and other bodies in the inner solar system.

Nearly the entire Moon is covered by a rubble pile of charcoal-gray, powdery dust and rocky debris called the lunar regolith. Beneath is a region of fractured bedrock referred to as the megaregolith. With too sparse an atmosphere to impede impacts, a steady rain of asteroids, meteoroids, and comets strikes the surface. Over billions of years, the surface has been ground up into fragments ranging from huge boulders to powder.

Science Advisor: Andrea Jones, NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center